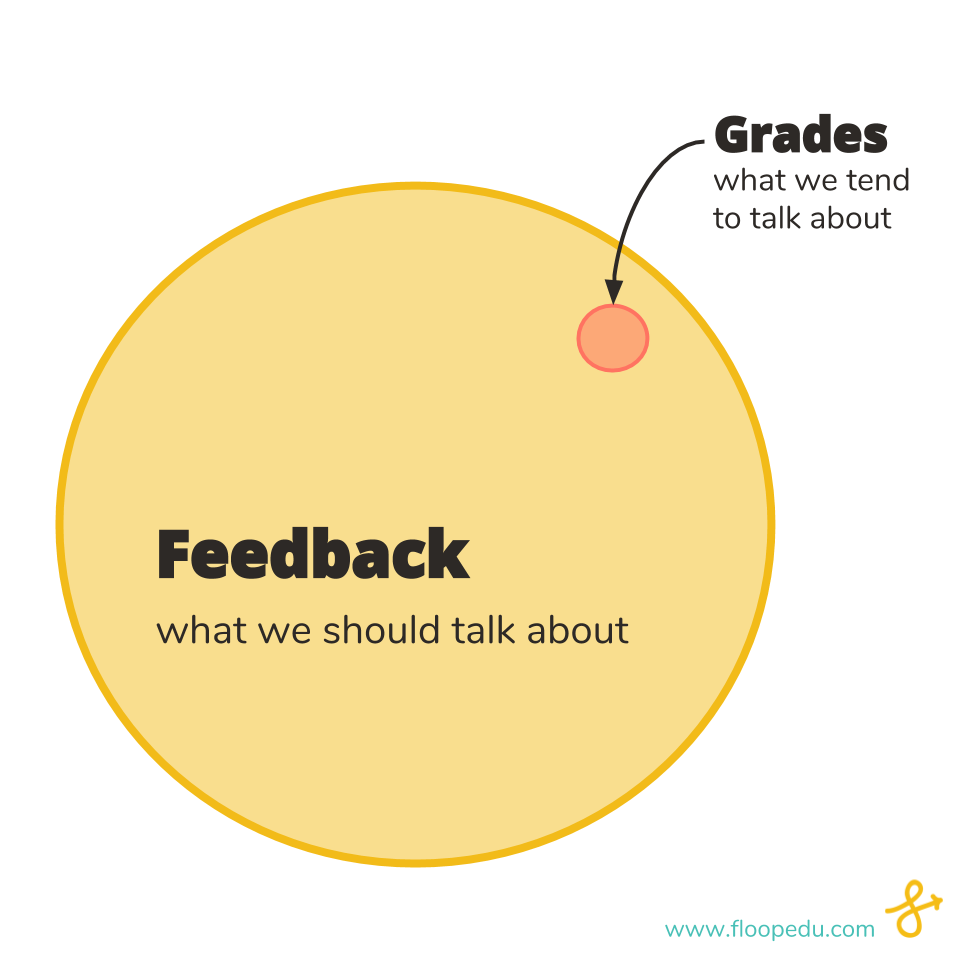

One question I ask other teachers is “How important is feedback in learning?” Every teacher I talk to agrees that feedback is crucial. It’s how both teacher and student gets better. Research backs the importance of feedback; building off of John Hattie’s work comparing factors on learning, Evidence for Learning’s toolkit ranks feedback as having the highest impact out of their 34 approaches (along with meta-cognition) with a +8 months’ impact on students’ learning progress.

I follow the feedback question with “How important are grades in learning?” It might seem like a loaded question. You can imagine how teachers respond: “They’re not.”

Why give grades, then? We’ll save that topic for another occasion. For now, I just want to point out that we are frequently asked to consider and describe our grading system by students, parents, colleagues, and administrators. We’re rarely asked about the much bigger and more important component of our work: feedback.

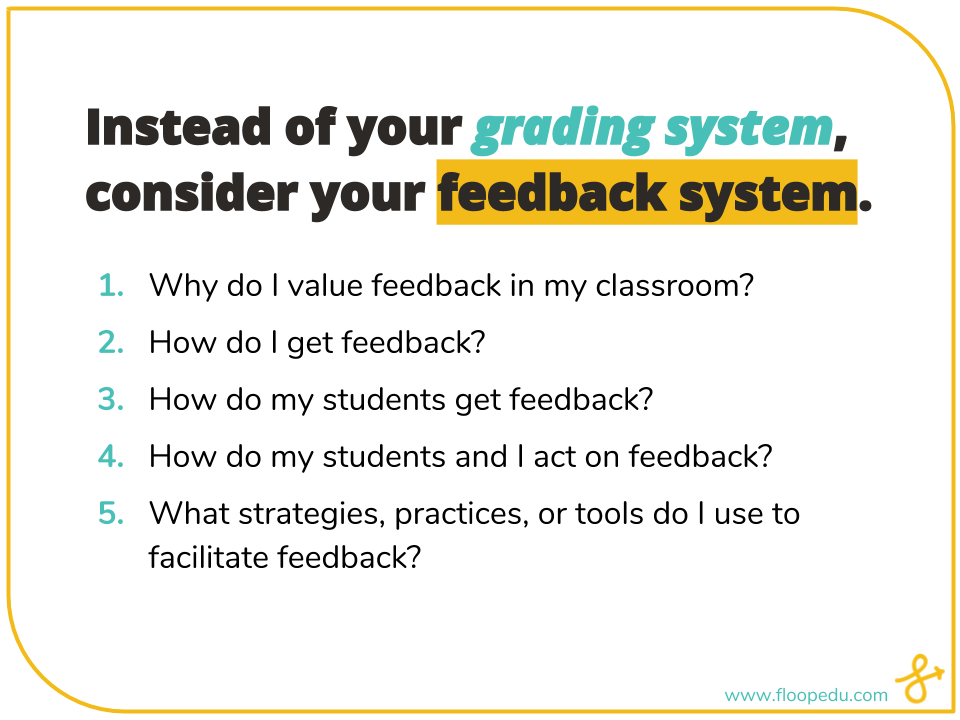

With back-to-school quickly approaching, now’s our chance to flip that narrative. Every student will get a copy of your syllabus, and grades tend to take up half of that document. I challenge you to replace that section of your syllabus this year. Instead of writing about your grading system, how about you write about your feedback system? Here are five questions you may consider:

Regardless of your grading system, your feedback system will encompass many possible strategies, practices, or tools. You could use paper trackers, your school’s learning management system (LMS), or a feedback tool like Floop. We’ll dive deep into specific feedback strategies later, but in the meantime, consider your current strategies for feedback.

---

I wrote out my feedback system for my HS Engineering / Entrepreneurship class last year. If you try writing out your own feedback system, let us know - we would love to share yours too!

What strategies do you have regarding feedback? How are you going to communicate your feedback system to students? Any other topics you want us to explore?

Keep us in the F(eedback)loop!

I follow the feedback question with “How important are grades in learning?” It might seem like a loaded question. You can imagine how teachers respond: “They’re not.”

Why give grades, then? We’ll save that topic for another occasion. For now, I just want to point out that we are frequently asked to consider and describe our grading system by students, parents, colleagues, and administrators. We’re rarely asked about the much bigger and more important component of our work: feedback.

With back-to-school quickly approaching, now’s our chance to flip that narrative. Every student will get a copy of your syllabus, and grades tend to take up half of that document. I challenge you to replace that section of your syllabus this year. Instead of writing about your grading system, how about you write about your feedback system? Here are five questions you may consider:

1. Why do I value feedback in my classroom?

Here’s where you set the groundwork. This is a philosophical question that’s worth asking yourself, even if you don’t end up communicating your feedback philosophy to students directly on your syllabus. What is the role of feedback in your classroom? Why do you spend time on feedback? What do you hope to accomplish in giving and receiving feedback?2. How do I get feedback?

Often we think about giving feedback to students, but it’s more important to get feedback. Getting feedback allows you to understand better where every student is and how you can meet his or her needs. In what ways will you actively seek feedback from your students? Assessments, especially ongoing formative assessment, can be a valuable source of feedback. Sometimes it’s quantitative, like tracking how many students get a question wrong, or sometimes it’s qualitative, like observing how a student succeeds or struggles on a task. You can also explicitly solicit feedback on your teaching practice from your students through discussions or surveys.3. How do my students get feedback?

Who provides feedback to students? As their teacher, you will be one source of feedback, but feedback could also come from the students themselves through self-evaluations, from their peers through peer-evaluation, or from outside mentors, coaches, and volunteers. What does this feedback look like? You could provide written or oral comments directly to students, but you could also have class discussions on general trends or show examples of student work. Then, how often do students receive feedback? Every teacher I talk to wants to give feedback more often, but there’s always a trade-off between the speed and the quality of that feedback. Coming up with an effective feedback system involves balancing different forms of feedback.4. How do my students and I act on feedback?

Once you’ve defined how you both you and your students will get feedback, the most important part of feedback is what happens after. What do you hope students do with feedback? Will students get a chance to demonstrate growth from feedback? If so, you’ll want to think about your processes around retakes, revisions, or re-assessments, and consider how you can spiral learning so there are multiple opportunities to demonstrate growth.5. What strategies, practices, or tools do I use to facilitate feedback?

Ah, here’s where grades might come up again. Grades can be a way to quickly communicate feedback to students. Maybe your grades are numbers, maybe they are letters, maybe they are a cool code that corresponds to Jedi mastery. Maybe you use categories and weights to let your students know what parts of the learning process you value over others. And maybe you’ve decided to just go gradeless / throw out grades and focus on the other parts of your feedback system. (There is both research and anecdotal evidence on the harmful effects of grades - more on that later.)Regardless of your grading system, your feedback system will encompass many possible strategies, practices, or tools. You could use paper trackers, your school’s learning management system (LMS), or a feedback tool like Floop. We’ll dive deep into specific feedback strategies later, but in the meantime, consider your current strategies for feedback.

---

I wrote out my feedback system for my HS Engineering / Entrepreneurship class last year. If you try writing out your own feedback system, let us know - we would love to share yours too!

What strategies do you have regarding feedback? How are you going to communicate your feedback system to students? Any other topics you want us to explore?

Keep us in the F(eedback)loop!

This speaks to me right where I am at in my quest to create a learning experience that hinges on mutual feedback throughout the learning process.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Daniel! Love the term "mutual feedback." Let me know how your quest goes!

ReplyDelete[…] post is part of a series challenging teachers to consider their feedback system for the new school year. I wanted to share my own feedback system as an example if it helps you […]

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing your info. I really appreciate your efforts

ReplyDeleteand I will be waiting for your next write ups thank you once

again.