Success in the real world depends on a person's ability to iterate.

As teachers, its our job to scaffold this process, with developmentally-appropriate differentiation, until our students can fly solo.

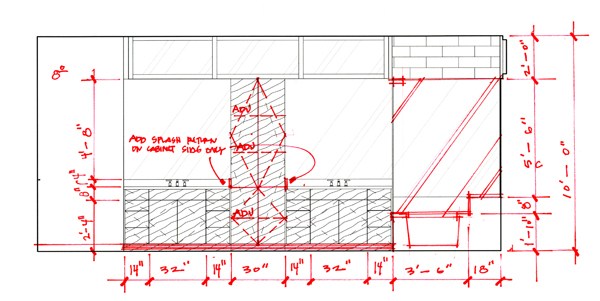

As I sit here writing this, my SO Dan is at his desk red-lining a building diagram for a warehouse in Canada. When he's done, the diagram will go back to his team of engineers where they will respond to Dan's feedback with a better design. They'll repeat this process until both building code and client requirements have been met. To do this work, which requires an iteration cycle that can last over a year or more, Dan has to understand building code and client needs, seek feedback from other engineers and the client, and use that feedback to revise and refine until the design is ready for implementation.

Dan wasn't born knowing how to do this at such a technical level. What did he learn along the way to prepare him for this iterative approach? What was he taught in college, high school, middle school that helped him get to where he is today? To hear him tell it, it was a frustrating journey that started too late and caused a lot of late nights when he hit graduate school.

Seeing where he is today and looking at the students sitting in my class has me wondering:

- to understand the definition of success on a task

- to seek feedback early and often

- to use that feedback to revise and refine until successful

As teachers, its our job to scaffold this process, with developmentally-appropriate differentiation, until our students can fly solo.

As I sit here writing this, my SO Dan is at his desk red-lining a building diagram for a warehouse in Canada. When he's done, the diagram will go back to his team of engineers where they will respond to Dan's feedback with a better design. They'll repeat this process until both building code and client requirements have been met. To do this work, which requires an iteration cycle that can last over a year or more, Dan has to understand building code and client needs, seek feedback from other engineers and the client, and use that feedback to revise and refine until the design is ready for implementation.Dan wasn't born knowing how to do this at such a technical level. What did he learn along the way to prepare him for this iterative approach? What was he taught in college, high school, middle school that helped him get to where he is today? To hear him tell it, it was a frustrating journey that started too late and caused a lot of late nights when he hit graduate school.

Seeing where he is today and looking at the students sitting in my class has me wondering:

What can we do in our classrooms to create a culture of iteration that will stay with our students for life?

Here's what I do

Keeping it simple, logical, and predictable.

Helping students understand the requirements for success:

- Every assignment is worth 10 points, which the students assign themselves through self-assessment. If it's a bigger assessment task, I break it into separate assignments with separate scores.

- Every assignment is graded on one, single skills standard. There are only 8 standards for the whole year and they're the same 6th through 8th grade. Only the content proficiency expectations change.

- Some assignments are also used as an assessment of a content standards. The feedback and scores for these are separated from the skills standards.

Supporting students in seeking feedback early and often

Students will always receive:

- A skills-specific mini-lecture when the task is assigned that is separate from any content instruction

- General group feedback at the start of the task

- Opportunities to practice with the assessment criteria through self-assessment or peer review.

- Specific, annotated, formative feedback on an individual level part-way through the task

- Generalized summative feedback upon completion of the task

Encouraging students to revise and refine until they are successful

- Any student may resubmit any assignment for up to full credit, as many times as they need, up through the end of the following unit.

FAQ

DOESN'T THIS CREATE A LOT OF EXTRA PAPERWORK FOR YOU?

Yes and no. Initially it did and that told me that I was assigning too many tasks in too short a time. If I can't keep up with giving the feedback, I can assume that they can't keep up with responding to it. I've scaled back the quantity and dialed up the quality of my assignments. In other words, I don't confuse busyness for rigor. I also use tech tools like Floop and Flash Feedback to help manage my workflow and improve the quality of feedback.DON'T STUDENTS SLACK OFF, KNOWING THEY CAN JUST DO IT AGAIN?

I thought this at first too and I found that, in general, this is really rare. I'll reserve the possibility that it's the demographic of my students, but I find that students recognize that doing the work again in a resubmit is more work than just doing it well the first time. I also don't hesitate to refuse to grade an assignment until a student improves the quality of the writing or presentation.DOESN'T THIS CAUSE GRADE INFLATION?

If your grading system is structured appropriately and your tasks are appropriately complex then student grades should reflect their proficiencies at the standards. If all of your students have scores at a proficient or mastery level by the end of the semester, that's not grade inflation -- that's great teaching!THIS DOESN'T REPRESENT THE REAL WORLD, YOU CAN'T JUST REDO THINGS AT WORK WHEN THEY DON'T GO WELL!

That's more of a cormorant than a question, but I'll bite. First, I think that we can all agree that our job as educators is to prepare our students for the "real world". This tenet rests on the premise that they are not yet ready for the "real world" and that we need to meet them where they are, often in One-draft-land, and bring them up to where they need to be (The Republic of Feedback-focused-iteration). Second, that is actually how the real world works. Otherwise, authors wouldn't need editors and scientists wouldn't need peer review panels.OK, BUT I TEACH HIGH SCHOOL AND/OR COLLEGE STUDENTS. HOW DO I TAKE OFF THE TRAINING WHEELS AND SCALE THIS THING UP FOR THEM?

I would recommend that you keep the cycle but shift up the timeline. Instead of allowing unlimited resubmits you may allow one resubmit for your 9th and 10th graders and then drop the resubmit policy for you 11th and 12th graders. If you choose to do this, make sure they you are offering opportunities for significant and substantial formative feedback from peers and from you.Your Turn

Consider your assessment policies and practices and ask yourself:

- Do they support students in understanding and, better yet, owning the definitions of success?

- Do they support students in regularly seeking useful feedback?

- Do they support students in implementing their feedback to improve their understanding and receive acknowledgement of their growth?

I enjoy your Twitter feed very much. I use an all-feedback-no-grades approach with college students, mostly seniors. It's ALL about iteration! Of course you can and should redo things... and making time for the redo is an important thing for students to learn IMO.

ReplyDeleteI just submitted a book chapter for a book about ungrading! I'll ping you when the book comes out; no timetable yet, but I am excited. Here's my chapter: Getting Rid of Grades.

Thanks, Laura! This resonates with me on so many levels. Particularly, when you talk about the punitive nature of grades and how the traditional grading system is at the root of problems with academic integrity. I really interested in the Declaration Quiz system you're using and I'm going to play around with how I could adapt this for my middle school classes. Thanks so much for sharing this with us and please let us know when it's published, I'd love to do a book review here!

DeleteI will be shouting it from every digital rooftop when it comes out! :-)

DeleteAnd of course I'll be seeing you at Twitter in the meantime...

Helpful post.

ReplyDelete