If you have 20 minutes in class, here’s a quick exercise to set expectations for student work. By showing student examples and facilitating a class discussion, I turned students' observations and feedback into their own list of expectations. In my class, students are working on documentation skills, but I can see this exercise for any repeated skill such as graphing in math, note taking in history, or writing lab reports in science.

Early on, I stress the importance of thorough documentation in Engineering. Students do an activity where they build cardboard cars given instructions, but the instructions are so bad that the cars totally flop! From there, we have a discussion about what should be included in thorough documentation.

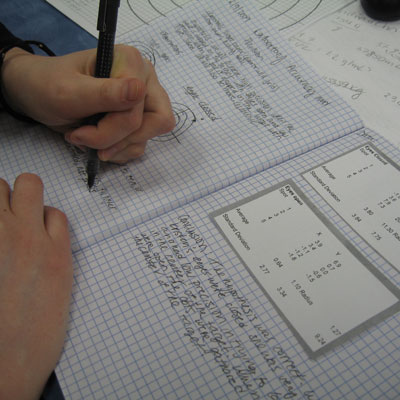

When they revised and redesigned the cardboard cars, they documented their new process. I gave them very little instruction and just two general mantras: 1) “If your mind was wiped, would you be able to recreate your own work?” and 2) “If it’s not in your notebook, it didn’t happen!” With those guidelines, I knew student products would look very different, but I hoped it would lead to more interesting discussion from which we could set expectations.

How do you set expectations with your students early in the year? Do you show student examples as a way to provide general feedback? How do you facilitate class discussions on feedback?

Keep us in the F(eedback)loop!

|

| Image courtesy of justonly.com |

Early on, I stress the importance of thorough documentation in Engineering. Students do an activity where they build cardboard cars given instructions, but the instructions are so bad that the cars totally flop! From there, we have a discussion about what should be included in thorough documentation.

When they revised and redesigned the cardboard cars, they documented their new process. I gave them very little instruction and just two general mantras: 1) “If your mind was wiped, would you be able to recreate your own work?” and 2) “If it’s not in your notebook, it didn’t happen!” With those guidelines, I knew student products would look very different, but I hoped it would lead to more interesting discussion from which we could set expectations.

What I did

- I asked students to submit their work. I assigned the work on Friday and reviewed their work on Sunday through Floop, but you could do the same thing with picking up papers.

- I quickly reviewed student work and then starred examples of high quality documentation. The reasons why I starred them were different. One entry had thorough instructions, another had clear diagrams, etc. but I made sure I had a number of different strengths illustrated with a variety of notebook styles.

- On Monday, I asked students to take out their own documentation. Then, I prefaced our class discussion with the disclaimer: There were so many examples of high quality documentation that I had a hard time choosing which ones to display, but I wanted to show a variety of different strengths and styles.

- I showed each example to the class. (I already had the photos loaded because of Floop, but I’ve done the same thing using a doc cam.) For each example, I asked students, “What do you like about this example? What do you notice?”

- From there, we created a class list of what students noticed/liked. I documented our class list to push back to the class.

- Now, students go back and revise! I told students that if they would like to revise their work, they have a few days to resubmit their documentation through Floop.

What I liked

Students saw a variety of high quality work with different strengths, organization, and neatness. I want for students to have autonomy in their notebooks but still keep a general framework in mind for high quality documentation. I also like that students will revise their first assignment; it sets the tone of the class for continuous growth and improvement.What I noticed

In previous years, I set expectations in advance for this assignment by having students create an initial outline of their documentation. The documentation would be more polished but very similar. This time around, there was more variation in quality, with some documentation incomplete but others exceeding expectations.What I’m curious about

How many students will revise their documentation, and what will they have taken from our discussion? Time will tell!How do you set expectations with your students early in the year? Do you show student examples as a way to provide general feedback? How do you facilitate class discussions on feedback?

Keep us in the F(eedback)loop!

Comments

Post a Comment