What could one author’s quest to avoid his afternoon cookie teach us about habit building in the classroom?

Last spring, I read Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit, a narrative-rich and comprehensive look at the brain science behind habit formation. And I started to think about how we use the word “habit” in our classrooms. Most of us have posters on our walls like, “Habits of a Mathematician” and “Habits of a Scientist.” But how well do we teach kids how habits really develop? Do we guide them in the kinds of reflections that will help them iterate on their strategies in meaningful and thoughtful ways?Duhigg’s Habit Loop Research in a Nutshell

Duhigg argues that people can change just about any habit when they're armed with the knowledge of how habits form in the brain. He recommends the following tips, summarized below, and also offers two flowcharts, one for How-to-Create-a-Habit and one for How-to-Change-a-Habit.

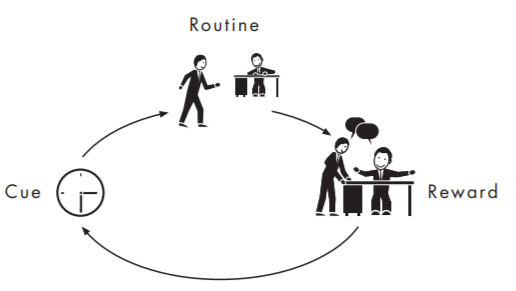

| Tip 1 | Understand the habit loop. The brain needs a cue, a routine, and a reward to build or sustain a habit. * |

| Tip 2 | Determine the cue. Cues can be a particular time of day or emotional state, or any number of other triggers. Duhigg’s classic example of wanting to change a habit began with his desire to lose weight. He couldn’t seem to break his daily habit of visiting the cafeteria to eat a cookie, so he began to examine his habit loop, beginning with the cue. He noticed that his cookie craving happened most days at around 3:30 pm and that he also felt bored and restless. |

| Tip 3 | Experiment with different rewards in order to understand your particular habit loop. Was Duhigg wanting the cookie for energy or because he was hungry? He tried replacing his cookie with coffee and then an apple and neither substitute worked. Then he discovered that the reward genuinely at play in his habit loop was socialization. The cookie routine had offered him an opportunity to see friends in the cafeteria. So that was it! He needed a new routine that still earned him the reward of socialization. |

| Tip 4 | Make your plan – After thoroughly understanding the cues and rewards in your particular habit loop, replace the routine with the behavior you want, keeping the cue and the reward the same. Make your plan and post it where you can see it often: "When I see [cue], I will do a [routine] to get a [reward]." Duhigg shared that his new habit loop looks like this. * Instead of visiting the cafeteria for a cookie in order to socialize, he now gets up and visits the desk of another co-worker to chat for a few minutes. Afterward, he feels better and is ready to work again.  |

After reading Duhigg’s book and perusing his web site, I was convinced that practicing his tips could help me improve my health. But could they also help my students learn new habits as writers and, in turn, improve their writing skills?

Like many teachers, I ask my students to set goals every fall, and then to reflect on their progress throughout the year. This is the start of what will become either a meaningful or obligatory series of reflections for the year. While many kids succeed in reflecting thoughtfully on a single assignment, most lose sight of reflecting also on their long-term goals and strategy adjustments.

My writing students also struggle with:

- Identifying meaningful goals. I will catch every spelling and punctuation error!

- Making plans they are motivated to use. I will give myself plenty of time for my writing assignments and read the rubric before, during, and after.

- Focusing less on the grade rather than on a specific change in strategy. I will earn a 90% or higher.

In an effort to help my kids take control of their progress in a more meaningful and iterative way, I’ll start by teaching Duhigg’s process.

Here’s a quick look at my habit-loop lesson plan.

- Assign “a habit video” for homework. Students will spend five minutes watching and 15 minutes responding to questions that will help them think about the content.

- Debrief students’ thinking via partner and whole-class sharing.

- Watch with students the first 5 minutes and the last 5 minutes of Duhigg’s TED talk. Note: this is a PG-rated video, so watch it ahead of time to be sure you’re sharing the portions you want to share and discuss.

- Share a teacher example of how I worked on changing a habit.

- Assign a Habit Formation Assignment with journal entries (due in three weeks).

- Have students reflect on their writing habits in a recent writing assignment, from pre-writing, drafting, feedback, revision, and editing. I'll ask them:

- What habits do you have as a writer right now?

- Which of your habits are already productive and which could change?

- What rewards motivate you, or could motivate you, in the different stages of the writing process?

- What alternate routines are possible in the cue-routine-reward loops

- Begin by setting a single SMART goal and making an action plan for the semester.

- As a part of your SMART goal, draw a habit loop [cue, routine, reward] that you might like to practice. Be sure to give yourself several routines to try, and focus on that reward!

I’ll let you know how it goes. 😊

For more lesson plan ideas on creating or changing habits, visit www.CharlesDuhigg.com.

[…] obstacle? The Character Lab suggests a when-then plan, but I can also see connecting this plan to a lesson on The Power of Habit to create a cue-routine-reward […]

ReplyDelete