We give our students a lot of feedback to guide their growth -- but do we do a good job of seeking and using feedback ourselves?

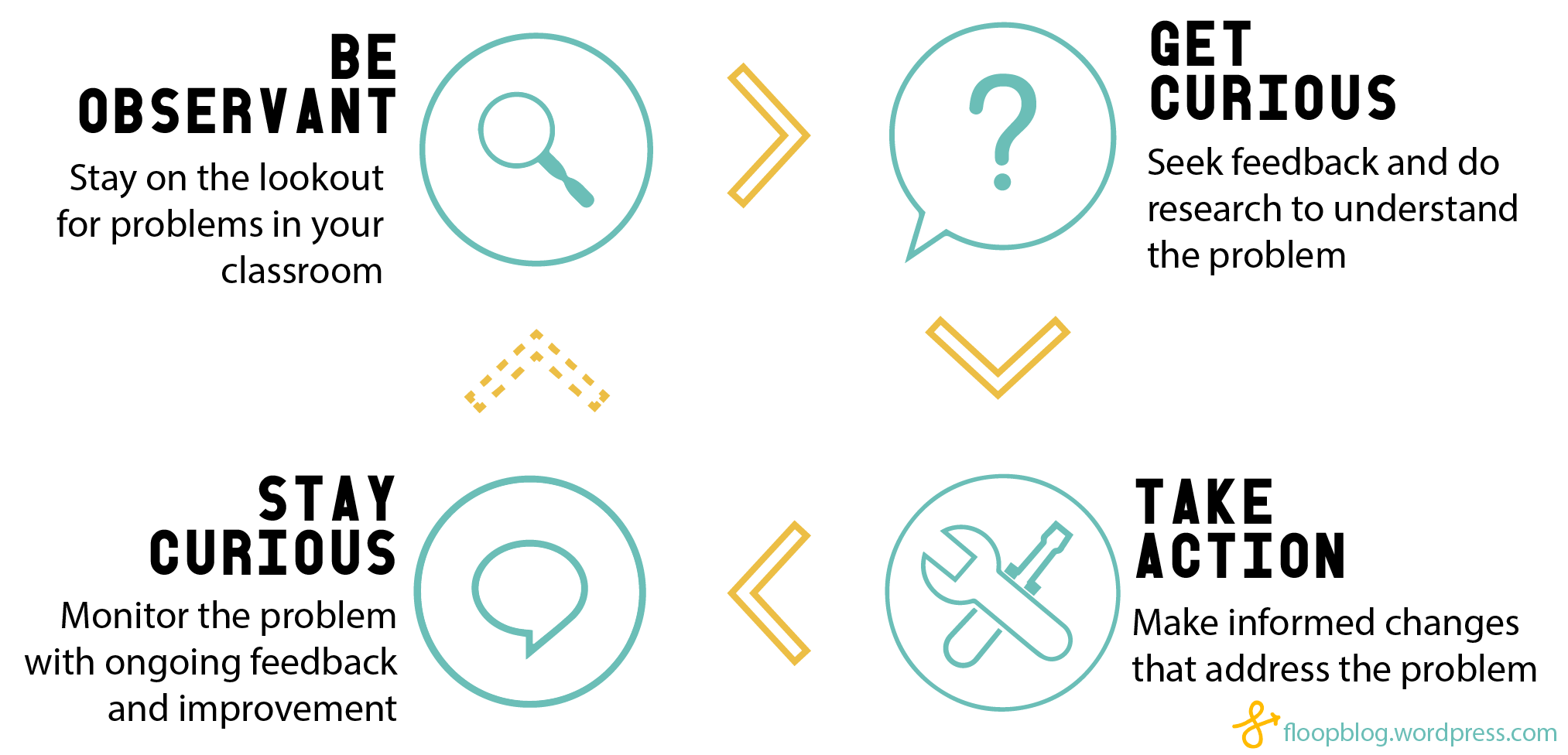

Over the winter break of 2015, I was somewhat startled to find myself searching the internet for career alternatives that would take me out of the classroom. I was feeling isolated in a room with students who didn’t want to engage with my class and was discouraged by a perceived lack of support from my administration.After a little rest and outdoor time, and a lot of Netflix, I realized that I didn’t need a different career -- I needed more feedback. Tapping into my knowledge of the Engineering Design Cycle, I envisioned a Teacher Feedback Loop that I could use to grow as a teacher.

Observing a Problem

The course that prompted this realization was a physical science course, consisting of three sections of 15-17 eighth grade girls. The previous summer I had started the 3-year UW Physics By Inquiry Summer Institute. The institute was a transformative experience and I came away from it excited to try inquiry instruction in my class during the 2015-16 school year. I was hopped up on the energy that comes from a new, promising instructional strategy and, I hate to admit, a small dose of the ego that also comes from having "discovered" a promising new instructional strategy.Unfortunately, reality had other plans. By winter my students ranged from patiently tolerant to disengaged to downright defiant, and parents and administrators were starting to get involved. I was seeing clear signs of what Seidel & Tanner call Student Resistance in response to my new teaching style:

“Behaviors and actions students take in a classroom situation when they become frustrated, upset, or disengaged from what is happening there.”

Getting Curious

Every time I thought about this class I felt defensive. I had a big problem and very little information. I realized that my attitude towards them was the same attitude they had towards me: we were all suffering from a lack of information. So I did for myself what any good scientist would do: I turned it into an experiment.This new perspective helped me switch my mindset from defensive to curious, and I decided to have my students take a survey. I designed a survey to answer the question:

What is the source of student resistance?I made the survey anonymous but mandatory, asking them to check their name off a list when they completed it. I also shared my motivation for the survey with my classes:

You'll notice that the questions are intentionally subjective:“As students, you get feedback all day about how you are doing and how you can improve. As a teacher, I don’t get as much feedback -- but I want to improve! This is the way that you can help me make this a better class and become a better teacher.”

- What about this class feels fair/unfair?

- What type of feedback do you get from Ms. Witcher? What additional feedback do you need?

- Other comments?

Unfair testing

“It felt unfair when there were questions on the quiz which were not taught in class or even the videos and textbook because often times I prepared well for the tests but never got the grade I thought i deserved.”

Unresponsive to students’ questions

“It feels like you play favorites you don't answer questions unless they were super specific.”

Apathetic to students

“I think that it is unfair how little class-to-teacher time we have. It feels like we are learning on our own, and not with a teacher, so there is really no point in the class at all. We could simply go online and learn everything that we learn in class.”

Taking Action

Armed with this wealth of data, I made a plan, choosing the most practical suggestions from Seidel & Tanner:| Decrease Social Distance between Yourself and Your Students | Be Explicit with Students about the Reasoning behind Your Pedagogical Choices | Vary the Teaching Methods Used |

|---|---|---|

| Incorporating mini-conferencing through homework “check-ins” with each student | Asking students to do guided research and conclude, “What is the best way to learn science?” | Incorporate peer review activities for writing assignments (this effort eventually turned into Flash Feedback!) |

| Giving more specific feedback on graded assessments (Floop has become a hugely useful tool for this effort!) | Working with the science department to develop a system of standards-based assessment | Starting each unit with a more guided introductory activity |

| Laughing with my students more | Explaining the purpose of every assessment as it is assigned | Incorporating authentic engineering design challenges |

Staying Curious

I gradually rolled out these strategies throughout the second semester, and then I monitored and adjusted. I continued with surveys twice a year to check in on student attitudes and experiences, and I continued to adjust my instructional and assessment practices in response. It wasn’t an overnight success. I've realized that I need to adopt a modified version of the The Customer is Always Right attitude: Is it true that I play favorites and only answer some students' questions? No. Is it true that something was causing this student to feel that way? Yes.Over the years, I've noticed some hopeful trends in the survey results. Overall, there’s been a transition from feedback concerning me as a person, to feedback concerning the course (and general lamenting about the challenges inherent to learning).

The best trend I’ve noticed is that the students increasingly respond to survey questions as if we’re all on the same team:

“The seating feels slightly unfair, but it is a very hard thing to figure out. I think it can also be sort of unfair when you can be trying really hard and being super on task, but then depending on whether or not the rest of the table is on task it can drag you down.”

This last school year, 2017-18, has been the best yet. I was ecstatic to see this graph at the end of the year:“There are not very many aspects that feel unfair. When we bring things to attention to Ms. Witcher, they are always addressed in a fair way.”

- Average student agreement: -2.0 = completely disagree, 2.0 = completely agree

"i had fun this year and enjoy knowing why stuff happens the way it does. thank you for a great year."

"this class is awesome!"

"it was a blast!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"

Your Turn

Thinking ahead to next school year, how can you implement a Teacher Feedback Loop to improve your teaching practice? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below:

What problem are you going to be working on in your classroom?

How might you get feedback to inform solutions to that problem?

Needed information for students.

ReplyDelete